Image of the month

Managing Dogs with Asymptomatic Calcium Oxalate (CaOx) Bladder or Urethral Stones

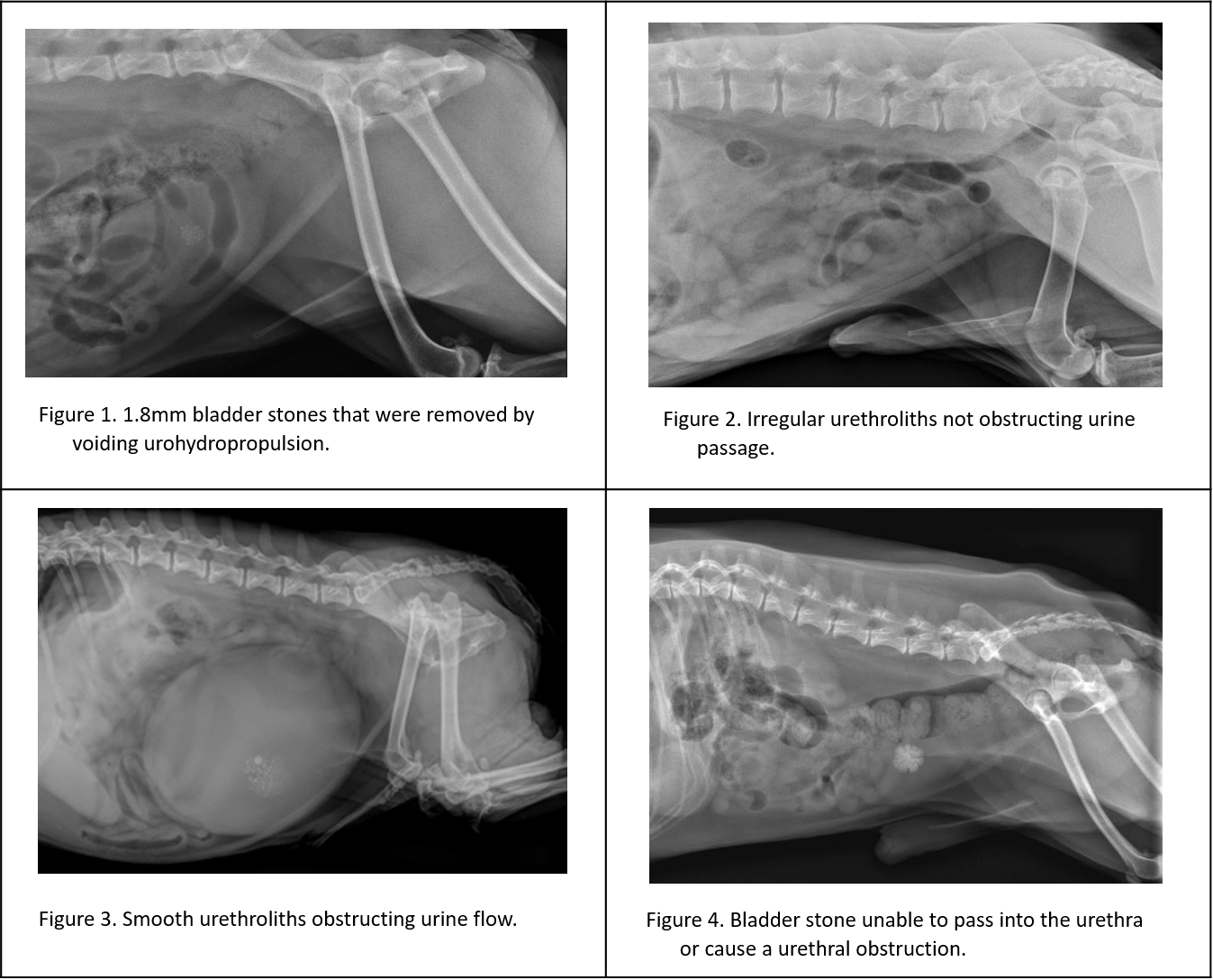

Calcium Oxalate stones are difficult to manage because they cannot be medically dissolved and recur often. When detected during routine abdominal imaging for other diseases (e.g. vomiting, orthopedic pain), stone removal is often recommended to avoid urinary obstruction and its life-threatening consequences. However, not all asymptomatic stones need to be removed at the time of diagnosis. Consider the following guidelines to avoid unnecessary or premature surgery.

| Stone Characteristic | Treatment Guideline | Rationale |

| Small stones capable of easily passing through the urethral lumen* (Figure 1) | Remove by voiding urohydropropulsion procedure videos | To avoid more invasive removal procedures and the possibility of urethral obstruction as stones grow, remove small stones early because spontaneous urolith passage is uncommon. |

| Irregular stones large enough to become trapped in the urethra but irregular enough to not obstruct urine flow (Figure 2) | Wait, watch, and remove stones when clinical signs develop# | Because calcium oxalate stones recur frequently, removing asymptomatic stones (that are too large to be removed by voiding urohydropropulsion) at the time of each diagnosis can result in more surgeries. |

Smooth stones large enough to become trapped in the urethra and smooth enough to completely obstruct urine flow (Figure 3)

| Consider stone removal. However, for clients with accessible 24-hour veterinary | Removing stones that can cause life-threatening obstruction can avert an unplanned emergency visit to the veterinarian. With time, stones will grow to a size incapable of passing into the urethra causing an obstruction. Therefore, waiting is an option. Communicating a management plan early will facilitate appropriate routine and emergency care, and ease client fears and improve patient outcomes. |

| Stones too large to enter into the urethra (Figure 4) | Wait, watch, and remove stones when clinical signs develop# | Stones unable to enter the urethra will not cause urinary obstruction. Because calcium oxalate stones recur frequently, removing asymptomatic stones (that are too large to be removed by voiding urohydropropulsion) at the time of each diagnosis could result in more surgeries. |

*In most dogs ≥ 5 Kg, stones <2mm in diameter in males and <3 mm in females can be removed by voiding urohydropropulsion. To accurately predict the feasibility of successful voiding urohydropropulsion, measure stone size radiographically and measure urethral diameter by successfully passing urinary catheters of know diameter (e.g., an 8 Fr catheter has a diameter of 2.7mm) to determine if stones are small enough to pass during voiding urohydropropulsion.

#If laser lithotripsy or percutaneous cystolithotomy is the preferred method of removal, remove stones before they are >7mm in diameter. Removal of larger stones may be associated with longer anesthetic periods or larger surgical incisions.