Research roundup: Is there a better way to catch Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease in children?

April 15, 2021

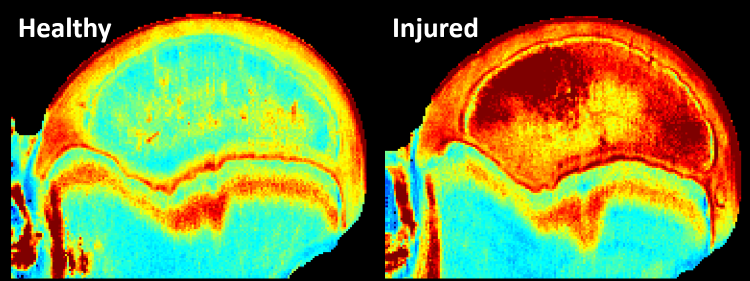

Researchers from three University of Minnesota colleges, including the College of Veterinary Medicine Department of Veterinary Clinical Sciences, and Scottish Rite for Children teamed up to determine if advanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) techniques that detect the dynamics of water molecules could detect early-stage bone damage in Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease (LCPD). All bones need blood to function, and the human circulatory system is designed to deliver it. But LCPD occurs when blood supply is temporarily cut off from the femoral head of the hip joint and the bone begins to die. The childhood disease typically strikes in kids between 4 and 10, and this young age limits the tools doctors can use to detect damage early, before bone cells die and cause permanent damage. MRI is the best technology available to diagnose LCPD, but the scans have limited ability to diagnose and predict clinical outcomes before the disease causes severe tissue damage. Using a contrast agent, such as gadolinium, can help doctors better determine the state of bone marrow on an MRI scan, but the method is not preferred for younger patients. The relaxation time mapping techniques used by this team of researchers enable MRI images to take noninvasive measurements of water content and composition of bone marrow and cartilage. Using a piglet model that has provided a foundation for successful LCPD human research, the researchers in the new study decided to test their theory on femurs from five piglets. The results were promising, showing that the two techniques the scientists used were able to detect early damage in removed piglet bones that model the acute avascular stage of LCPD. Now, the researchers are calling for next phase research on live animal models and then people. The findings could one day be used to better detect early-stage damage caused by LCPD, as well as other bone and joint disorders, in children.

Read more in the article published March 21 in the Journal of Orthopaedic Research.

Image courtesy of Casey Johnson, PhD